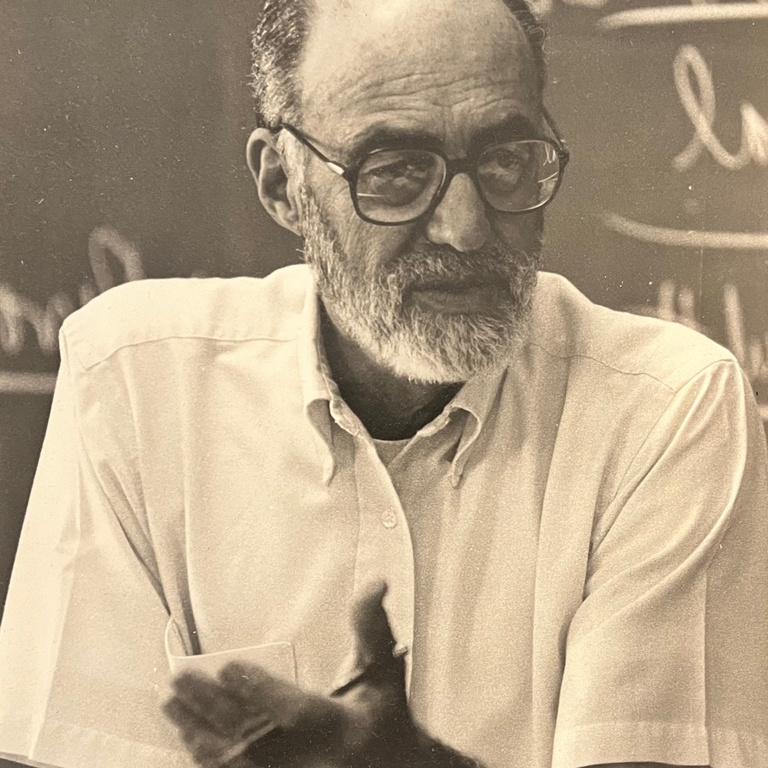

Alan Spitzer (1925 – 2024)

Alan Spitzer’s scholarship placed him in the front rank of historians of the Restoration period in France. His books, including, The Revolutionary Theories of Louis-Auguste Blanqui (Columbia University Press, 1957); Old Hatreds and Young Hopes:The French Carbonari Against the Bourbon Restoration (Harvard University Press, 1971) and The French Generation of 1820 (Princeton University Press, 1987) established him as a major interpreter of the revolutionary currents that animated the Bourbon Restoration period in French history.

His work led him to critically examine the ways in which generational experience, not aging per se, marks the development of historically consequential political ideology and activism. As both an intellectual and social historian he melded the history of ideas and quantitative social science methods to document the animating ideas and the social boundaries faced by a revolutionary generation, what he termed “the generation of 1820.” Spitzer provided an astute and critical rendering of the conflicting interpretive currents of generational analysis in “The Historical Problem of Generations,” American Historical Review, vol. 78, No. 5, December 1973, and of the “moral choice” behind the disciplinary standards for historical truth-telling in a volume of essays, Historical Truth and Lies About the Past (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), published after he retired from teaching.

Alan Spitzer served as president of the Society for French Historical Studies in 1982-1983 and on the editorial boards of the Journal of Modern History and French Historical Studies. He held fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the Woodrow Wilson Center, and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. In 1979-1980 he was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study.

Alan B. Spitzer was born in Philadelphia on March 27, 1925. He graduated from Central High School and attended Penn State University before enlisting in the army at age 18 in 1943. His moving reminiscence of his war experience – wounded not long after his first experience of combat in November 1944 – appears in The Palimpsest, a journal of the State Historical Society of Iowa, Winter 1995. As he wrote in that essay, he was haunted all his life by the “malevolent ingenuity” through which humans have slaughtered one another.

After recovering from his war wounds, Alan resumed his studies at Swarthmore College, graduating in 1948, and pursued graduate study at Columbia University, receiving a PhD in 1955. He first taught in the School of General Studies at Boston University for four years, before joining the History Department at the University of Iowa, where he taught for the rest of his career, retiring in 1992. In 1989, he was awarded the University’s Faculty Achievement Award for Excellence in Teaching.

When the times required a thoughtful moral and critical presence on campus, he spoke out forcefully in 1965 as a faculty member against the war in Vietnam. He engaged a generation of student activists, coordinated a conference on civil rights (1964), led the effort to form a “free university” (1968), and chaired a committee advocating the end of funding for the war (1970). He insisted that university space is public space dedicated to tolerance and free speech. He chaired a “Joint Committee for Amnesty” on behalf of all those facing legal retribution for opposition to the war in Vietnam. No one who was present when he chaired a mass meeting on behalf of amnesty in early 1974 will forget how he managed to facilitate an occasion for reasonable people on both sides to articulate their deep commitments.

Alan Spitzer was highly regarded and recognized by his peers as an outstanding teacher of undergraduates and graduates. His innovative teaching was characterized by the incorporation of nontraditional kinds of evidence – the iconography of World War I posters and of medals from the revolutions of 1848—and guiding students through hands-on analysis of quantitative data on arrests and casualties among members of nineteenth-century French crowds.

In the 1970s, Alan Spitzer invented, nurtured and sustained a fresh alternative to the standard Western Civilization course. Instead of lectures to hundreds of students, “Problems in Human History” introduced undergraduates to the study of history in a seminar setting, taught by the department’s most experienced and gifted graduate students. With a dedicated cadre of graduate teaching assistants, Alan helped to create new thematic “problems” courses, carefully read and took seriously student evaluations, and sustained a model for quality general education in a large public university.

Alan was an avid fly fisherman in the streams and rivers of the West. He enjoyed hiking in national parks, was enthusiastic about playing golf, and a lover of jazz and blues.

He is survived by his wife, Mary F. Spitzer, sons Mark and Robert, three grandchildren, and four stepchildren. He was preceded in death by his first wife, Anne Larcher Spitzer, in 1997.

Written by Linda K. Kerber and Shelton Stromquist, The University of Iowa

Additional obituary from family

Research areas

- French Intellectual History